High Iron

For more than a hundred years an obscure granite pyramid was the only monument to the transcontinental railroad in Wyoming. The Ames Monument, completed in 1882, memorializes a couple corrupt railroad financiers, but makes no mention of the laborers who actually built the tracks. In September 2024, a new monument opened to the public in contrast to the Ames brothers’ ungracious obelisk. High Iron is a 42-foot long train car turned public art and oral history exhibit - a monument to stories of railroad labor, stories of community, and stories of place from across the landscape.

The collaboratively-created public art project features an interactive labor exhibit, oral history collection station, murals, and art installations that together serve as a hub for community programming. High Iron shares stories of the multigenerational and multicultural laborers, immigrant families, and a history of caring. In 2025, the project will continue to deepen its storytelling in connecting with other rail towns as well as Indigenous artists whose ancestral connection to the land predates the tracks and the changes that the railroad brought with it.

High Iron

For more than a hundred years an obscure granite pyramid was the only monument to the transcontinental railroad in Wyoming. The Ames Monument, completed in 1882, memorializes a couple corrupt railroad financiers, but makes no mention of the laborers who actually built the tracks. In September 2024, a new monument opened to the public in contrast to the Ames brothers’ ungracious obelisk. High Iron is a 42-foot long train car turned public art and oral history exhibit - a monument to stories of railroad labor, stories of community, and stories of place from across the landscape.

The collaboratively-created public art project features an interactive labor exhibit, oral history collection station, murals, and art installations that together serve as a hub for community programming. High Iron shares stories of the multigenerational and multicultural laborers, immigrant families, and a history of caring. In 2025, the project will continue to deepen its storytelling in connecting with other rail towns as well as Indigenous artists whose ancestral connection to the land predates the tracks and the changes that the railroad brought with it.

My role in the project

I worked as a member of High Iron’s creative team alongside friends and collaborators Aubrey Edwards and Laura Zorch McDermit. In my role I served as a leader for the project’s five-member artist team, as a graphic designer, and as a contributing visual artist. I managed workflow for the artist team, facilitated creative consensus-building discussions, and helped to troubleshoot installation of artworks on a fast five-month timeline. Creating art for High Iron came with a significant amount of research into the railroad’s history as well as my own ancestral ties to railroad labor. Pictured here is my great great grandpa Pierce Anders, who worked as a locomotive fireman.

My role in the project

I worked as a member of High Iron’s creative team alongside friends and collaborators Aubrey Edwards and Laura Zorch McDermit. In my role I served as a leader for the project’s five-member artist team, as a graphic designer, and as a contributing visual artist. I managed workflow for the artist team, facilitated creative consensus building discussions, and helped to troubleshoot installation of artworks on a fast five-month timeline. Creating art for High Iron came with a significant amount of research into the railroad’s history as well as my own ancestral ties to railroad labor. Pictured here is my great great grandpa Pierce Anders, who worked as a locomotive fireman.

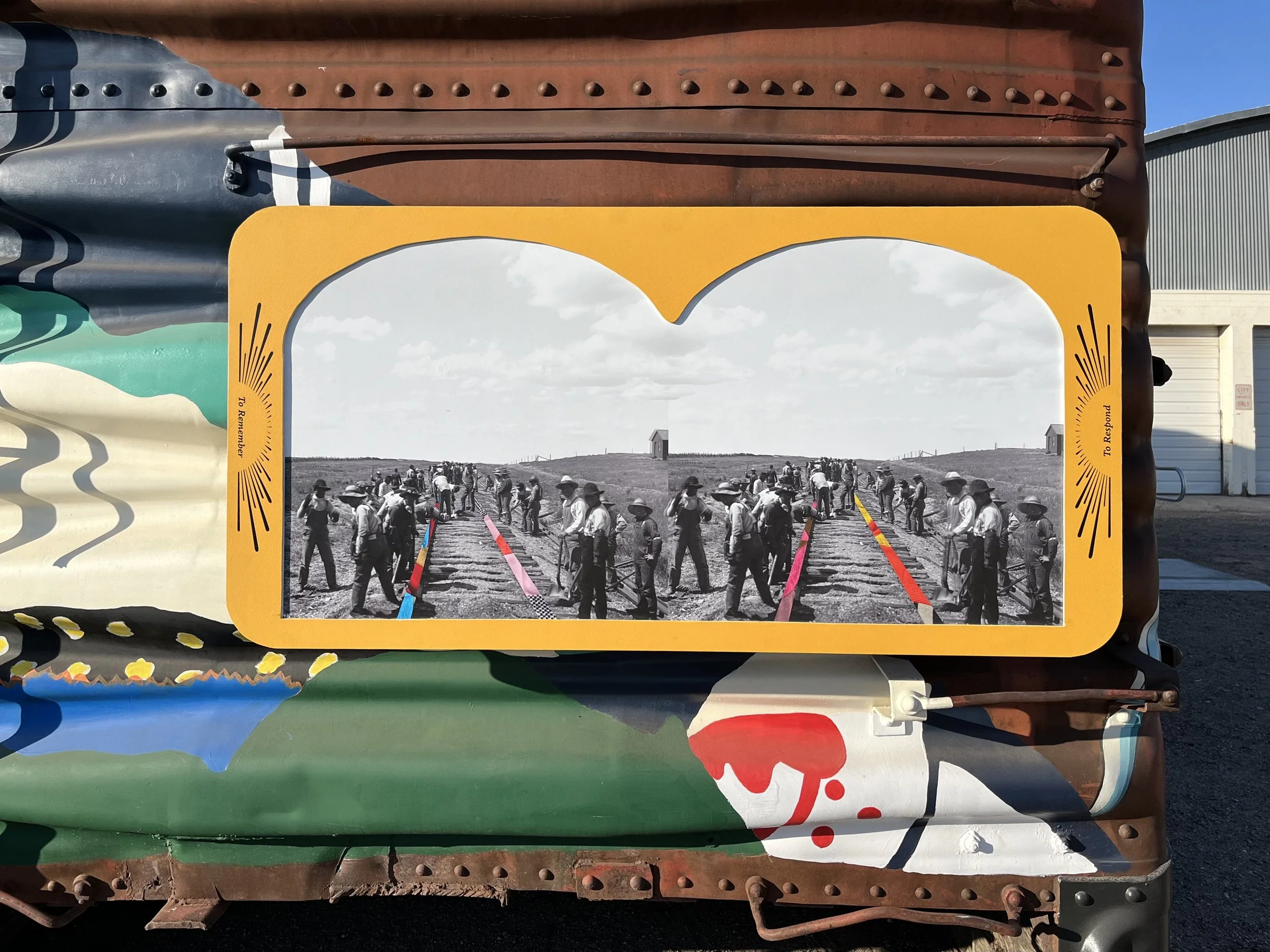

Remember and Respond mimics the look and feel of an old stereograph, but on a larger scale and with the collaged, mirrored use of Joseph Stimson’s 1906 photo of a Japanese section crew working not too far from Laramie. The colors running down the tracks rhyme with fellow artist Eirini Linardaki’s style, while borrowing patterns from a quilt belonging to one of our project collaborators, Lena Newlin. Lena is a fourth generation Wyomingite, a descendent of early Japanese American railroaders, and one of several community members who graciously shared family history with High Iron. (J.E. Stimson photo courtesy of Wyoming State Archives)

Remember and Respond mimics the look and feel of an old stereograph, but on a larger scale and with the collaged, mirrored use of Joseph Stimson’s 1906 photo of a Japanese section crew working not too far from Laramie. The colors running down the tracks rhyme with fellow artist Eirini Linardaki’s style, while borrowing patterns from a quilt belonging to one of our project collaborators, Lena Newlin. Lena is a fourth generation Wyomingite, a descendent of early Japanese American railroaders, and one of several community members who graciously shared family history with High Iron. (J.E. Stimson photo courtesy of WY State Archives)

Sea Change is a lenticular print combining two historical images of the bison, including James Fraser’s ‘Buffalo Nickel’ (1913) and Eadweard Muybridge’s ‘Buffalo Galloping’ (1887). Walking past the work the image shifts from a photo of one of the last original members of the Great Plains’ bison herds, to a photo of its five-cent replica. Gunmen, traders, merchants, and industry made massive profits off bison hides in the early days of the railroad, and when the species was decimated, they made exponentially more from bison bones covering the prairie.

Sea Change is a lenticular print combining two historical images of the bison, including James Fraser’s ‘Buffalo Nickel’ (1913) and Eadweard Muybridge’s ‘Buffalo Galloping’ (1887). Walking past the work the image shifts from a photo of one of the last original members of the Great Plains’ bison herds, to a photo of its five-cent replica. Gunmen, traders, merchants, and industry made massive profits off bison hides in the early days of the railroad, and when the species was decimated, they made exponentially more from bison bones covering the prairie.

Leading the Artist Team for High Iron has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my in my public art career. Artists Eirini Linardaki, Amanda Pittman, Anjel Garcia, Karen Vaughan, Michael Chavez, and myself worked together to develop a values-driven, consensus-building creative framework for the project that combined individual visions with a collective voice. Seeing a group of emerging and established artists come together to accomplish such a feat in just five months pays homage to the speed and determination of those who built the transcontinental railroad across Wyoming.

Working in Community

The project would not be possible without the help of the many community members who contributed their skills and stories to realizing the vision of High Iron. Carpenters, painters, crane operators, welders, and electricians all worked with different members of the team on renovations, fabrication, and installation of artworks, while the Sanchez & Vigil, Matsamura & Sunada, and Angeli & Englert families all shared stories, photos, letters, and other mementos honoring their connection to Laramie through rail labor. High Iron will continue with this deep community centered work for years to come, in connecting with laborers, creatives, storytellers, and families across the state.

Project Website

Explore the box car and learn more at: www.highiron.org

Creative and Artist Teams

Aubrey Edwards, Laura Zorch McDermit, Conor Mullen

Visual Artists: Amanda Pittman, Anjel Garcia, Karen Vaughan, Eirini Linardaki, Michael Chavez, Conor Mullen

Exhibit and Opening Reception Photographer: Elena Ricci